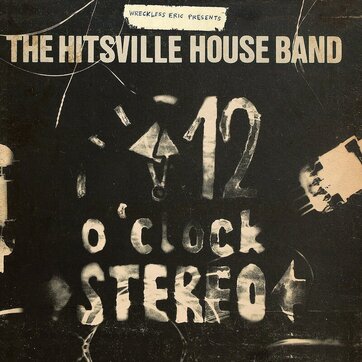

12 O'Clock Stereo - The Hitsville House Band 1996

|

ERIC GOULDEN (WRECKLESS ERIC) - succession of clapped-out guitars and organs, vocal DENIS BAUDRILLART - drumset and maracas FABRICE LOMBARDO - double bass, bass guitar

with MICHAEL LEMBACH - trumpet CHRISTOPH LINDER -tenor and baritone saxophones ANDRE BARREAU - extra guitar (The Girl With The Wandering Eye, Camden Girl, Miriam) harmonies (Palace Of Tears, Camden Girl, The Twilight Home, Miriam, Can't See The Woods)

with MICHAEL LEMBACH - trumpet CHRISTOPH LINDER -tenor and baritone saxophones ANDRE BARREAU - extra guitar (The Girl With The Wandering Eye, Camden Girl, Miriam) harmonies (Palace Of Tears, Camden Girl, The Twilight Home, Miriam, Can't See The Woods)

I needed a touring band. In economic terms I needed a touring band as much as I needed a hole drilling in my head, but I was tired of touring solo and tired of people saying 'if you're this good just on your own imagine how good it'd be with a band...'

I wanted a band that was homespun, into the DIY ethic, a band that could get into using a vocal PA, do wacky pop-up shows and record in my shack in the French countryside. Really I wanted another Len Bright Combo.

I called my Mexican bass playing friend from Paris, Eduardo Leal de la Gala. Eduardo played on If It Makes You Happy on The Donovan Of Trash album. He was in a band I formed and toured with briefly as a substitute for the Beat Group Electrique. We toured in Europe for a short while and fell out. In those days Eduardo and I were good at falling out, I hope that's all behind us now.

He came over and we ran through some tunes – Kilburn Lane, Can't See The Woods (For The Trees) and an embryonic version of Zero To Minus One which never actually arrived on a record until the 2012 Wreckless Eric & Amy Rigby album, A Working Museum, even though it featured in early Hitsville House Band sets.

I loved playing with Eduardo – he had a homemade fretless bass constructed from part of a table top and the neck and electrics from a Gibson EB bass copy which I had given him.

We searched around for a drummer and came across Denis Baudrillart, a moody Parisien with a gold Hayman drum kit and a matching gold suit. He had immaculate hair that fell across his face as he played, giving him a look of unrestrained violence.

We toured Europe for three months on the back of The Donovan Of Trash album and got quite good - a ramshackle band with barely adequate equipment travelling in an unreliable Volkswagen minibus that used to belong to a girls school choir and still had the logos to prove it.

We came home ready to make a new album but Eduardo had extreme financial difficulties so he took a job in a bank and this meant he had no time to come out to the countryside to record.

By the time Eduardo was finished working all hours and was available again I'd bought a Studer A80 1” eight track machine from the BBC. It cost seven hundred pounds, a small fortune for me at the time – generally I strolled around with less than twenty pounds in my pocket and that would be all the money I had in the world. I lived a hand to mouth existence punctuated by twice yearly publishing royalty payments and the odd lucrative tour date. Upgrading from quarter inch four track to one inch eight track was a huge step forward.

The Studer was a beast of a thing, it weighed as much as a Mini Cooper. I picked it up from the BBC Redundant Plant depot in Power Road, Chiswick. It was unceremoniously tipped on its side onto a pallet and lifted into my Volkswagen minibus with no thought as to how I might get it out. I drove down to Newhaven at speeds approaching forty five miles an hour, caught the ferry and trundled home along French country roads with the suspension near breaking point.

The village schoolteacher, Monsieur Frederique, helped me to slide the thing out of the van and get it onto its wheels – fortunately it was on wheels. Monsieur Frederique said it was tres interessant and I headed him off with some rubbish about looking after it for a friend. I didn't want anyone knowing what went on in the former village dance hall. I got it into the house through the garage and had to remove two doors, two door frames and a bannister to get it into the studio.

During the time that Eduardo was unavailable Denis and I had been playing with Martin Stone in his country / r 'n' b / psychedelic band. Martin had a great double bass player, Fabrice Lombardo, who had played with him in Almost Presley (who backed me on Harry's Flat on The Donovan Of Trash).

As soon as I had the Studer wired up Denis and Eduardo came over to record. The results were disappointing. The sound was great but the playing wasn't. We did take after take, song after song, and nothing sat right. In Eduardo's absence Denis and I had got used to playing with Fabrice who seemed to be able to play anything without a problem. Sadly, Eduardo was out of practice and his heart didn't seem to be in it.

I was approached to record a track for a compilation album called Love Is My Only Crime so I wrote a song called Ugly & Old. There was a deadline and Eduardo couldn't make it so we got Fabrice to come and record the track. The difference was astounding – we nailed Ugly & Old in two takes with Fabrice on upright bass and me on acoustic guitar fitted with an electric guitar pick-up bolted across the sound hole. I plugged it straight into the desk. I did the vocal live, even though we were crammed into a small room with a full drum kit – the same room where I'd recorded The Donovan Of Trash.

To make the trip worthwhile we recorded a backing track for Friends On The Floor, and as that only took three takes we knocked out Kilburn Lane with Fabrice on bass guitar. We rehearsed the song and got it in one take.

I knew a good thing when I saw it so I asked Fabrice if he'd do the whole album and he said he'd be delighted. Of course I had to deal with the consequences. I had a terrible row out with Eduardo which I regretted for years, but I think we both know it was the right thing to do.

The studio was much improved from the Donovan Of Trash days. I'd put in soundproofing and lined the walls with sheet rock. The room had the most disgusting suspended ceiling: lengths of 2 x 1 suspended with chains from the ceiling with six inch thick Rockwool panels laid across the top. It worked very well but it made the room dark, hot and claustrophobic.

We set the drums up in a corner of the room lined with red and grey aircraft ceiling panels liberated from a nearby factory that fabricated that sort of thing. The panels were made with sound insulating foam sandwiched between two sheets of aluminium covered with thick red or grey vinyl. The room had a sound - dry but not dead. I can hear the sound of that room on the album.

I recorded the drums with one Sennheiser dynamic microphone plugged into a Leak tube pre-amp. No mic on the bass drum, it didn't need it – Fabrice played facing the kit and the bass drum resonated through the body of the double bass and into the amplifier which sat on the floor next to me behind the console.

We recorded basic tracks, bass, drums and guitar, in several sessions. It seemed to take ages, recording through the winter and spring of 1993, fitting in sessions between my solo tour dates and gigs with Martin Stone.

Fabrice and Denis had a job at Euro-Disney playing in a rockabilly band. It was well paid but they hated it – they had to wear stretch polyester slacks and lamé jackets, a Disney version of Sun Records. The outfits were often crumpled in a grubby heap in a corner of the van.

The sessions were quite relaxed – we'd work on two or three songs and record two or three versions of each one. Some of them we got in a couple of takes, others we kept coming back to. You Can't Be A Man (Without A Beer In Your Hand) took take after take, session after session. The drawback of having a French band was that they couldn't always find the groove within the lyric though they'd usually get things really quickly, I'd tell them to follow my guitar and quite often I'd put down a live vocal. You Can't Be A Man and Palace Of Tears were difficult because they were both hinged around a riff which at the time I couldn't play while I was singing.

After every session I was left with tracks to work on. I played my increasingly temperamental Hammond organ on Murder In My Mind, The Twilight Home and The Marginal. I used every guitar I owned - a 1966 Gibson 330, a Hofner Club 60, the famous green Microfret, an art deco Supro, a Supro lapsteel in mother of toilet seat finish, a homemade acoustic that may have been someone's school woodwork project...

I used a variety of amplifiers but mostly a 12 watt Watkins Scout (I wish I still had it). I quite often changed guitars in the middle of an overdub, and sometimes made a composite of two or more guitar takes played using different guitars and amplifiers. I tried to keep things casual even though I often got myself into a high old state with the voices of imagined critics and detractors ringing in my ears. After two albums with The Len Bright Combo followed by Le Beat Group Electrique and The Donovan Of Trash I'd developed a thick skin but I still suffered from moments of paranoia and self-doubt.

Andre Barreau came over for a couple of days to help out with vocal harmonies and more guitar bits. It was a very cold weekend in January and we spent most of the time holed up in the studio, even when we weren't actually recording. It was the warmest place to be. An American photographer had been round and photographed me for an article in a Swiss magazine. She bought some large coloured lights with her, and rather than carry them back to Paris on the train she donated them to the studio where they effected quite a transformation – the austere hell hole cum laboratory was transformed into a warm, cosy and creative place and became my favourite room in the house, which was just as well because I was spending most of my time in there.

I always think of 12 O'Clock Stereo as my town and country album, a strange and at times uneasy mix of garage, pop, country and old time rhythm 'n' blues.

Kilburn Lane came from a wet and violent night in Kilburn. Before we went on a large, drunken man with an accordion took the stage – he sat on a chair, mumbled a few words, and with a loud exclamation tore the accordion in half and fell backwards through the drum kit. During the load out we tried to stop a man from kicking a woman to death. The pair of them turned on us. I remember playing the harmonium on that track – the harmonium was in the hallway so I had to put the machine in record and rush out into the hallway, pump the thing up, play the part and run back in to stop the machine before the next track got erased.

I put a brass section on some of the tracks, saxophone and trumpet. I'd never recorded brass before so there was a certain amount of bluff involved.. I didn't have charts, or even a music stand to put them on, I put microphones in the corridor and sang an approximation of the parts to them.

I suddenly realised the recordings were finished – or at least there were enough recorded songs to make an album. By this time I had a stereo mixing desk but I only had a mono mastering machine - an all-valve Telfunken one track 1/4” mono tape machine that recorded one track across the entire width of 1/4” tape. It had previously been used in a jungle expedition, as borne out by the carcasses of large and weird looking insects reclining in the machinery. It was a hundred degrees in the studio and at one point the machine caught fire. I mixed all twelve tracks in a week during a heatwave.

I'd known all along that the album was going to be in mono – the stereo possibilities are immediately limited when you record the drums with one microphone – you could put the drums to one side or create a stereo picture with the other instruments around a mono drum kit. And anyway, I like mono – pan pots in the centre position: 12 O'Clock Stereo.

I wanted a band that was homespun, into the DIY ethic, a band that could get into using a vocal PA, do wacky pop-up shows and record in my shack in the French countryside. Really I wanted another Len Bright Combo.

I called my Mexican bass playing friend from Paris, Eduardo Leal de la Gala. Eduardo played on If It Makes You Happy on The Donovan Of Trash album. He was in a band I formed and toured with briefly as a substitute for the Beat Group Electrique. We toured in Europe for a short while and fell out. In those days Eduardo and I were good at falling out, I hope that's all behind us now.

He came over and we ran through some tunes – Kilburn Lane, Can't See The Woods (For The Trees) and an embryonic version of Zero To Minus One which never actually arrived on a record until the 2012 Wreckless Eric & Amy Rigby album, A Working Museum, even though it featured in early Hitsville House Band sets.

I loved playing with Eduardo – he had a homemade fretless bass constructed from part of a table top and the neck and electrics from a Gibson EB bass copy which I had given him.

We searched around for a drummer and came across Denis Baudrillart, a moody Parisien with a gold Hayman drum kit and a matching gold suit. He had immaculate hair that fell across his face as he played, giving him a look of unrestrained violence.

We toured Europe for three months on the back of The Donovan Of Trash album and got quite good - a ramshackle band with barely adequate equipment travelling in an unreliable Volkswagen minibus that used to belong to a girls school choir and still had the logos to prove it.

We came home ready to make a new album but Eduardo had extreme financial difficulties so he took a job in a bank and this meant he had no time to come out to the countryside to record.

By the time Eduardo was finished working all hours and was available again I'd bought a Studer A80 1” eight track machine from the BBC. It cost seven hundred pounds, a small fortune for me at the time – generally I strolled around with less than twenty pounds in my pocket and that would be all the money I had in the world. I lived a hand to mouth existence punctuated by twice yearly publishing royalty payments and the odd lucrative tour date. Upgrading from quarter inch four track to one inch eight track was a huge step forward.

The Studer was a beast of a thing, it weighed as much as a Mini Cooper. I picked it up from the BBC Redundant Plant depot in Power Road, Chiswick. It was unceremoniously tipped on its side onto a pallet and lifted into my Volkswagen minibus with no thought as to how I might get it out. I drove down to Newhaven at speeds approaching forty five miles an hour, caught the ferry and trundled home along French country roads with the suspension near breaking point.

The village schoolteacher, Monsieur Frederique, helped me to slide the thing out of the van and get it onto its wheels – fortunately it was on wheels. Monsieur Frederique said it was tres interessant and I headed him off with some rubbish about looking after it for a friend. I didn't want anyone knowing what went on in the former village dance hall. I got it into the house through the garage and had to remove two doors, two door frames and a bannister to get it into the studio.

During the time that Eduardo was unavailable Denis and I had been playing with Martin Stone in his country / r 'n' b / psychedelic band. Martin had a great double bass player, Fabrice Lombardo, who had played with him in Almost Presley (who backed me on Harry's Flat on The Donovan Of Trash).

As soon as I had the Studer wired up Denis and Eduardo came over to record. The results were disappointing. The sound was great but the playing wasn't. We did take after take, song after song, and nothing sat right. In Eduardo's absence Denis and I had got used to playing with Fabrice who seemed to be able to play anything without a problem. Sadly, Eduardo was out of practice and his heart didn't seem to be in it.

I was approached to record a track for a compilation album called Love Is My Only Crime so I wrote a song called Ugly & Old. There was a deadline and Eduardo couldn't make it so we got Fabrice to come and record the track. The difference was astounding – we nailed Ugly & Old in two takes with Fabrice on upright bass and me on acoustic guitar fitted with an electric guitar pick-up bolted across the sound hole. I plugged it straight into the desk. I did the vocal live, even though we were crammed into a small room with a full drum kit – the same room where I'd recorded The Donovan Of Trash.

To make the trip worthwhile we recorded a backing track for Friends On The Floor, and as that only took three takes we knocked out Kilburn Lane with Fabrice on bass guitar. We rehearsed the song and got it in one take.

I knew a good thing when I saw it so I asked Fabrice if he'd do the whole album and he said he'd be delighted. Of course I had to deal with the consequences. I had a terrible row out with Eduardo which I regretted for years, but I think we both know it was the right thing to do.

The studio was much improved from the Donovan Of Trash days. I'd put in soundproofing and lined the walls with sheet rock. The room had the most disgusting suspended ceiling: lengths of 2 x 1 suspended with chains from the ceiling with six inch thick Rockwool panels laid across the top. It worked very well but it made the room dark, hot and claustrophobic.

We set the drums up in a corner of the room lined with red and grey aircraft ceiling panels liberated from a nearby factory that fabricated that sort of thing. The panels were made with sound insulating foam sandwiched between two sheets of aluminium covered with thick red or grey vinyl. The room had a sound - dry but not dead. I can hear the sound of that room on the album.

I recorded the drums with one Sennheiser dynamic microphone plugged into a Leak tube pre-amp. No mic on the bass drum, it didn't need it – Fabrice played facing the kit and the bass drum resonated through the body of the double bass and into the amplifier which sat on the floor next to me behind the console.

We recorded basic tracks, bass, drums and guitar, in several sessions. It seemed to take ages, recording through the winter and spring of 1993, fitting in sessions between my solo tour dates and gigs with Martin Stone.

Fabrice and Denis had a job at Euro-Disney playing in a rockabilly band. It was well paid but they hated it – they had to wear stretch polyester slacks and lamé jackets, a Disney version of Sun Records. The outfits were often crumpled in a grubby heap in a corner of the van.

The sessions were quite relaxed – we'd work on two or three songs and record two or three versions of each one. Some of them we got in a couple of takes, others we kept coming back to. You Can't Be A Man (Without A Beer In Your Hand) took take after take, session after session. The drawback of having a French band was that they couldn't always find the groove within the lyric though they'd usually get things really quickly, I'd tell them to follow my guitar and quite often I'd put down a live vocal. You Can't Be A Man and Palace Of Tears were difficult because they were both hinged around a riff which at the time I couldn't play while I was singing.

After every session I was left with tracks to work on. I played my increasingly temperamental Hammond organ on Murder In My Mind, The Twilight Home and The Marginal. I used every guitar I owned - a 1966 Gibson 330, a Hofner Club 60, the famous green Microfret, an art deco Supro, a Supro lapsteel in mother of toilet seat finish, a homemade acoustic that may have been someone's school woodwork project...

I used a variety of amplifiers but mostly a 12 watt Watkins Scout (I wish I still had it). I quite often changed guitars in the middle of an overdub, and sometimes made a composite of two or more guitar takes played using different guitars and amplifiers. I tried to keep things casual even though I often got myself into a high old state with the voices of imagined critics and detractors ringing in my ears. After two albums with The Len Bright Combo followed by Le Beat Group Electrique and The Donovan Of Trash I'd developed a thick skin but I still suffered from moments of paranoia and self-doubt.

Andre Barreau came over for a couple of days to help out with vocal harmonies and more guitar bits. It was a very cold weekend in January and we spent most of the time holed up in the studio, even when we weren't actually recording. It was the warmest place to be. An American photographer had been round and photographed me for an article in a Swiss magazine. She bought some large coloured lights with her, and rather than carry them back to Paris on the train she donated them to the studio where they effected quite a transformation – the austere hell hole cum laboratory was transformed into a warm, cosy and creative place and became my favourite room in the house, which was just as well because I was spending most of my time in there.

I always think of 12 O'Clock Stereo as my town and country album, a strange and at times uneasy mix of garage, pop, country and old time rhythm 'n' blues.

Kilburn Lane came from a wet and violent night in Kilburn. Before we went on a large, drunken man with an accordion took the stage – he sat on a chair, mumbled a few words, and with a loud exclamation tore the accordion in half and fell backwards through the drum kit. During the load out we tried to stop a man from kicking a woman to death. The pair of them turned on us. I remember playing the harmonium on that track – the harmonium was in the hallway so I had to put the machine in record and rush out into the hallway, pump the thing up, play the part and run back in to stop the machine before the next track got erased.

I put a brass section on some of the tracks, saxophone and trumpet. I'd never recorded brass before so there was a certain amount of bluff involved.. I didn't have charts, or even a music stand to put them on, I put microphones in the corridor and sang an approximation of the parts to them.

I suddenly realised the recordings were finished – or at least there were enough recorded songs to make an album. By this time I had a stereo mixing desk but I only had a mono mastering machine - an all-valve Telfunken one track 1/4” mono tape machine that recorded one track across the entire width of 1/4” tape. It had previously been used in a jungle expedition, as borne out by the carcasses of large and weird looking insects reclining in the machinery. It was a hundred degrees in the studio and at one point the machine caught fire. I mixed all twelve tracks in a week during a heatwave.

I'd known all along that the album was going to be in mono – the stereo possibilities are immediately limited when you record the drums with one microphone – you could put the drums to one side or create a stereo picture with the other instruments around a mono drum kit. And anyway, I like mono – pan pots in the centre position: 12 O'Clock Stereo.